How to decide whether an investment is worth your money

- Gianmarco Forleo

- 24 mar 2019

- Tempo di lettura: 6 min

NET PRESENT VALUE AND BOOK RETURNS

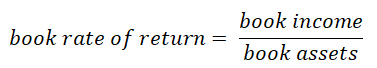

Financial managers, when preparing the financial statement for shareholders, calculate the book rate of return that is the ratio between the income the investment will generate and the cost of the asset that has to be acquired:

Book income and cashflow are generally different because the book assets (representing the cost to buy the investment) depend on what the financial managers will consider as capital investments. Some expenses may in fact be considered as operating expenses.

THE PAYBACK

The payback period of a project is the time that the investment will need to completely pay back the initial cost. If you decide that you want to invest money in a project that will give you back the full investment in 3 years, according to the payback rule you will choose investments that offer payback periods lower than 3 years. It does not matter whether the investment you are considering will produce more cashflows in the years after the third because, with that rule, you will accept only projects that satisfy the initial condition. Furthermore the payback rule gives equal importance (no discounts so you do not have to depreciate anything while applying it) to all the cashflows before the cutoff date, meaning that two projects may pay the investment back in the same year and therefore having the same importance with the payback rule but really different net present values. The cutoff rule can be also bad if used in a non-correct way: if you do not decide a cutoff date enough far in time, you will not consider a lot of long run really profitable projects but you will instead consider a lot of short run, low profitable projects. If are interested in knowing after which period the investment will repay its costs considering opportunity costs and therefore discount, you need just to sum the present value of all the cashflows until the NPV becomes positive.

THE INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN

When you are considering an investment that will produce a single cashflow in the future you can calculate its rate of return as:

Alternatively we can find the discount rate that makes the present value of the investment equal to 0. The NPV is computed as follows:

The discount rate making the NPV=0 is called the discounted cashflow (DCF) rate of return or the internal rate of return (IRR). Because the IRR is the discount rate making NPV = 0 in order to find it for a project lasting more than one year we need to solve the following expression:

In order to decide whether to consider or not an investment, you should compare the IRR with the opportunity cost of capital. According to the internal rate of return rule, you should invest if and only if IRR >opportunity cost of capital. If this happens, when you discount your investment using as discount factor the opportunity cost, the NPV of the investment will be greater than 0 while, if IRR<opportunity cost, you will have a negative NPV. This is true for all the investments that present a declining IRR as the discount rate increases, so, the more you discount them the less is their present value. Most investments that are about a cash-out today for a cash-in tomorrow, have this property because the more you discount future

periods, the more you discount the earnings.

The IRR rule alone presents however some problems:

1)NO DISTINCTION BETWEEN POSITIVE OR NEGATIVE CASHFLOWS

Consider the two investments depicted in the picture, as you can see both of them have IRR=50% but they have completely different NPV. This is because in the first case, you are lending money, thus receiving more money in the future and therefore earning a profit. In the second case, you are borrowing money and therefore making a negative profit. To the IRR both the options are the same, no matter which is the final NPV. The second project has an upward sloping net present value as we increase the discount rate. This is because, the more you discount the future cashflows, the less you will pay.

2)NON UNIQUE RATE OF RETURNS

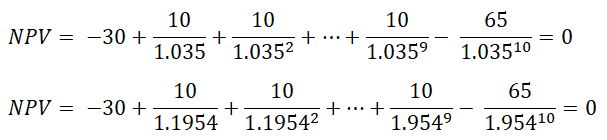

Imagine that you want to build a factory that will be in use for 10 years (producing cashflows for only 9 of them) and then has to be shut down and that, not only you will have to pay to build the factory in the beginning, but also to shut it down after the 10 years. The cost to build the factory is $30 million and the factory will produce $10 million a year when in use and then, to be shut down it requires $65 million. The NPV of the investment is 42.53 millions but notice that both the equations are correct:

So both 3.5% and 19.54% are acceptable IRR. This happens because the cashflows change sign two times, the first one passing from – to + between period 1 to period and the second when passing from + to – between period 9 and 10. The more times an investment produces different sign of cashflows, the more IRR you will find.

CHOICES BETWEEN TWO OR MORE PROGECTS

When you have to choose one among two or more investments, the IRR could not be the best way to do so. Consider two investments as the ones depicted in the table below.

As you can see, even if the first has a lower NPV, if you only compare IRR you will choose it over the second. This happens because the first investments promises higher returns in terms of percentage but lower returns in terms of absolute values. Remember that it is better having 1% of $1 million than 100% of $50. If you want to go around the problem, you should consider if the additional investment is worth it: subtract from the cashflows of the “bigger one” the cashflows of the “small one” and now look whether the IRR is positive.

In this case because the IRR is 50% it is worth spending more money on the most expensive project.

Another problem with the IRR is that a project that has higher time horizon may have a lower IRR then a shorter period with a lower PV. Many people, if they think there is a shortage of capital, will choose investments like the second one because they will be scared that they will not find more funds in the future. But the optimal situation even in those cases is to use NPV to evaluate projects.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU HAVE DIFFERENT OPPORTUNITIES COST OF CAPITAL

Suppose that each period has its own opportunity cost of capital so each period cashflow is discounted with a different discount factor:

In order to use the internal rate of return rule, we need a single discount factor and therefore it is necessary to compute a complicated weighted average to do so.

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU HAVE LIMITED RESOURCES

Suppose that, as in most cases in real life, you have to choose among different projects because you do not have enough money to carry on them all. In this case you will face a capital rationing decision.

Suppose that you can choose among the projects depicted above but that you have only $100,000 available. If this is the case, you can not blindly aim at the projects that have the highest present value but you have to aim at the project that will generate more income per dollar spent. This is measured by the profitability index computed as follows:

Notice that, even thought the first investment has the highest present value, the others have higher profitability index and their present value combined is higher than the one of the first investment and therefore you should buy the second and the third one instead of just the first one.

Suppose now that the firm can only spend $100,000 in the present and the future (so $100,000 in T=0 and $100,000 million T=1) and suppose the investments cashflows as depicted in the table:

A strategy could be the one of accept project B and C that have the highest profitability index. This combination has a present value of $280,165 but we can do better. If we accept only offer A in period 0 then we will be able to spend in period 2 the $100,000 as annual budget and also the $300,000 thanks to investment A and therefore we will be able to accept project D. This combo A+D gives a NPV of $346,281.

Soft rationing is the situation in which the firm imposes to its divisions a certain amount of capital they can spend in order to control them better and to not incur in severe losses in cases of bad management. In this situation we are considering an “ideal” situation because if the firm wants to increase the money available for each division it can easily do so. With hard rationing we refer to a situation in which the firm, even if it wants to, can not raise any money. This could happen for example in those cases where investors or banks do not trust enough the firm to lend it a large sum of money.

Commenti